Cross-Compiling C++ Projects with dockcross

Cross-compilation has a huge impact on the development of cross-platform C++ embedded software. Therefore we have plenty of tools to help us, and dockcross is one of them, which we will briefly discuss.

|

|---|

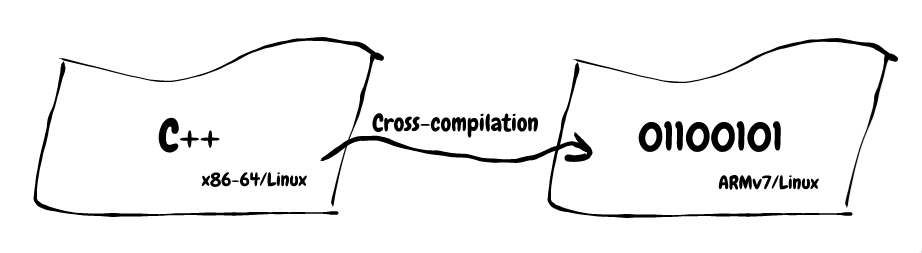

| Cross-compiling C++: x86-64/Linux -> ARMv7/Linux. sketchpad.io |

Software that executes on a different platform than the one we used to write it has to be cross-compiled.

When we refer to “compiling”, we usually mean the act of converting our source-code into a representation that the machine understands, ultimately a bunch of zeros and ones.

Often, we execute our program on an equivalent platform to the one we used to write and compile it. Say, my development laptop has an x86-64 architecture running Linux, and my program will execute on yet another x86-x64 architecture running Linux, perhaps the same laptop used for development.

However, if we want to execute our program on a different platform than the one we used for development, then things get a little different. Say again, my development laptop with an x86-64 running Linux, but my program will execute on a Raspberry Pi with an ARMv7 architecture running Linux.

In the latter scenario, we have a mismatch between the development platform (host) and the execution platform (target). Thus, a program compiled for my host will not execute on the target. We need to cross-compile our code from the host to the target.

The term “platform” is an abstraction, it may mean the processor architecture, operating system, C library, combination of them, etc. When we have a mismatch between host and target platforms, we need to cross-compile the code on the former so that it can execute on the latter. In this discussion, we will only consider the processor architecture (x86-64 vs ARMv7) as therefore we might treat processor architecture as a synonym to the platform. For more details, please refer to GNU Triplet.

To cross-compile to a different platform, we need a cross-toolchain.

Cross-toolchains

Our C++ source-code goes through a series of transformations before yielding the final executable, approximately:

- The pre-processor expands directives (lines starting with

#) presented in the source-code to generate translation-units. - The compiler compiles the translation-units down to assembly instructions.

- The assembler assembles the assembly (quite a funny phrase!) instructions into “incomplete” (lacking dependencies) binaries.

- The linker links our “incomplete” binaries with their dependencies to generate the final (“complete”) executable.

Each step in the sequence (“chain”) is normally performed by a specific tool. Hence the set of tools used by the chain receives the name “toolchain”.

A toolchain is a set of distinct software development tools that are linked (or chained) together by specific stages such as GCC, binutils and glibc [1].

When the host platform differs from the target platform, we then need a cross-toolchain that knows how to generate code that our target understands. As a side-note, when the host and target platforms do match, we then have the so-called native-compilation, which is performed with a native-toolchain. Since native-compilation is the usual scenario and therefore implied, we don’t usually need the “native” prefix.

We sometimes refer to the whole build chain as “compilation”, and often to cross-toolchain as a cross-compiler. That should be fine™.

We need a cross-toolchain for each specific platform where would like to execute our program on, say ARMv7 + Linux.

There are plenty of ways to get a toolchain. Generally, they boil down to (i) compile one from sources, (ii) use a pre-built toolchain.

Compiling a toolchain from sources might give us more control over the whole process, at the expense of a steeper learning curve. On the other hand, pre-built toolchains might grant us less control but are usually easier to get things up-and-running. Consequently, there’s no right choice here, that’s intimately related to your requirements.

In the following sections, we will use a pre-built toolchain from dockcross to show how we can quickly get a toy C++ project cross-compiled for ARMv7 and executed on a Raspberry PI 3 (rpi3). Additionally, we will execute our cross-compiled program in an emulator running on our development machine, again, using dockcross.

Example: Native-compiling

As a basic example, we have a C++ executable with a unit-test and a dependency on GoogleTest. The build is orchestrated with CMake, generating all build artifacts into the build directory. The whole procedure takes place on an x86-64 development machine running a Linux Distribution.

Layout:

$ tree -L 1

.

├── build

├── CMakeLists.txt

└── main.cpp

main.cpp:

#include <gtest/gtest.h>

auto add(int const x, int const y) -> int {

return x + y;

}

TEST(add, OnePlusOneEqualsTwo) {

ASSERT_EQ(add(1, 1), 2);

}

CMakeLists.txt:

To keep the scope small, we are integrating GoogleTest into our project with CMake’s

FetchContentinstead of a proper package manager (e.g Vcpkg or Conan).

cmake_minimum_required(VERSION 3.14)

project(dock-cross-example CXX)

include(CTest)

include(FetchContent)

FetchContent_Declare(

googletest

GIT_REPOSITORY https://github.com/google/googletest.git

GIT_TAG release-1.10.0

)

FetchContent_MakeAvailable(googletest)

add_executable(app main.cpp)

target_compile_features(app PUBLIC cxx_std_11)

target_link_libraries(app gtest gtest_main)

add_test(app app)

Before we get into the cross-compilation dance, let’s first compile it natively:

$ cmake -Bbuild/ && cmake --build build/

Inspecting the executable at build/app, we might see:

$ file build/app

build/app: ELF 64-bit LSB shared object, x86-64, version 1 (GNU/Linux), dynamically linked, interpreter /lib64/ld-linux-x86-64.so.2, for GNU/Linux 3.2.0, BuildID[sha1]=f35671505ce650eaddd04652011d5c6ed5fa23e2, not stripped

That says that our executable is built for the x86-64 architecture and expects the interpreter at /lib64/ld-linux-x86-64.so.2.

Lastly, by executing the program, we should see something along the following lines:

$ ./build/app

Running main() from /dock-cross-example/build/_deps/googletest-src/googletest/src/gtest_main.cc

[==========] Running 1 test from 1 test suite.

[----------] Global test environment set-up.

[----------] 1 test from add

[ RUN ] add.OnePlusOneEqualsTwo

[ OK ] add.OnePlusOneEqualsTwo (0 ms)

[----------] 1 test from add (0 ms total)

[----------] Global test environment tear-down

[==========] 1 test from 1 test suite ran. (0 ms total)

[ PASSED ] 1 test.

That’s it!

We now want to cross-compile the same program and be able to execute it on our rpi3, shall we?

Example: Cross-compiling with dockcross

As we said before, we need a cross-toolchain that runs on our x86-64/Linux and generates an executable, which can then execute on our Raspberry PI 3 with ARMv7/Linux. An easy way to get a cross-toolchain up and running is by using dockcross.

Essentially, dockcross offers C and C++ pre-built and configured cross-compiling toolchains for several different platforms as Docker images. By using Docker, we can isolate build tools and artifacts and keep our development work-flow clean. And with a bit of discipline, reproducible.

To get-started with dockcross, we must have Docker installed. Then, we can fetch a cross-toolchain for ARMv7/Linux with the following commands:

$ docker run --rm dockcross/linux-armv7 > ./dockcross-linux-armv7 && chmod +x ./dockcross-linux-armv7

That should result in the script dockcross-linux-armv7, which we gave permissions to execute it. That’s our entry-point to cross-compiling and much more.

dockcross-linux-armv7 receives commands and runs them inside a Docker container, which ships with a pre-built and configured cross-toolchain that we can then use to cross-compile for ARMv7/Linux. Additionally, the Docker container comes with other tools commonly used for C++ development, e.g. CMake.

Let’s cross-compile our project and put the build artifacts into the build_armv7 directory:

$ ./dockcross-linux-armv7 cmake -Bbuild_armv7/

$ ./dockcross-linux-armv7 cmake --build build_armv7

For demonstration purposes, I did not specify the image version. However, in the real world, we probably want reproducible builds, and therefore we should pin a specific image version, or even stricter, its hash.

That’s it!

Inspecting the executable at build_armv7/app, we might see:

$ file build_armv7/app

build_armv7/app: ELF 32-bit LSB executable, ARM, EABI5 version 1 (GNU/Linux), dynamically linked, interpreter /lib/ld-linux-armhf.so.3, for GNU/Linux 4.10.8, with debug_info, not stripped

Among other things, that says that our executable is built for the ARM architecture and expects the interpreter at /lib/ld-linux-armhf.so.3

We can now transfer it to a rpi3 and execute it:

$ (pi) /tmp/app

Running main() from /work/build_armv7/_deps/googletest-src/googletest/src/gtest_main.cc

[==========] Running 1 test from 1 test suite.

[----------] Global test environment set-up.

[----------] 1 test from add

[ RUN ] add.OnePlusOneEqualsTwo

[ OK ] add.OnePlusOneEqualsTwo (0 ms)

[----------] 1 test from add (0 ms total)

[----------] Global test environment tear-down

[==========] 1 test from 1 test suite ran. (0 ms total)

[ PASSED ] 1 test.

Bingo!

Furthermore, quite a few images shipped by dockcross come with emulators. Thus we can execute our cross-compiled program on our development machine:

$ ./dockcross-linux-armv7 bash -c './build_armv7/app'

Running main() from /work/build_armv7/_deps/googletest-src/googletest/src/gtest_main.cc

[==========] Running 1 test from 1 test suite.

[----------] Global test environment set-up.

[----------] 1 test from add

[ RUN ] add.OnePlusOneEqualsTwo

[ OK ] add.OnePlusOneEqualsTwo (1 ms)

[----------] 1 test from add (2 ms total)

[----------] Global test environment tear-down

[==========] 1 test from 1 test suite ran. (5 ms total)

[ PASSED ] 1 test.

That’s neat! Think of unit-tests as part of the CI process.

Conclusion

We’ve discussed the role that cross-compiling plays in embedded software development. We briefly saw what a toolchain is. Then we glanced over dockcross, which gave us a pre-built cross-compiling toolchain that we later used to cross-compile a toy C++ example and even executed it in an emulator running on our development machine.

In our example, we cross-compiled for the Raspberry Pi. However, dockcross has support for many other cross-toolchains, which are available in different Docker images.

Additionally, dockcross ships with more tools that can be useful in the development process. Therefore, I’d encourage to check the documentation and give it a try.

Moreover, dockcross is just one possible option, and not the single option. Hence, we may also want to consider other solutions as well, for instance crosstool-NG, raspberrypi/tools, a fully-fledge Yocto, Nix, roll our own Docker images, etc.

Furthermore, it might worth exploring how the tooling around other programming languages support cross-compilation, e.g Rust’s cross or Go’s GOOS/GOARCH:

cross build --target armv7-unknown-linux-gnueabihf # Rust (+ cross).

GOARCH=arm GOOS=linux go build # Go.

Perhaps we could adapt some ideas to C++. Or, depending on your requirements, consider developing with one of those languages.

Happy cross-compiling!

References

[1] dockcross.