A type-system imposes discipline on programs. And we can make the best out of it by employing correct, precise, and expressive types; ultimately even letting the type-system assisting us in our design. Equipped with well-crafted user-defined types, we can then make some illegal states unrepresentable.

Additionally, types are great to disambiguate and communicate ideas to fellow programmers.

|

|---|

| Types impose constraints and enforce invariants. sketchpad.io |

Functional Programming comes with its vocabulary (actually, any programming paradigm, for what’s worth), and oftentimes we might be able to figure out everything that is to be known about a higher-order function just by looking at its name.

Consider map as an example:

map :: (a -> b) -> [a] -> [b]

Give me a function of type

a -> band a list of elements of typea, then I shall return you a list of elements of typeb.

The name map already indicates that we “map over a thing”, where “thing” here means a list of elements of some generic type a. Other than its name, the API exposed by map has another interesting aspect worth mentioning: its type.

Even if map were called magic, we could guess what it does:

magic returns a list of elements of type b. But it has to work for all types b that users of magic will ever pass in, without exceptions.

Hence magic can’t just conjure up a value of type b out of thin air. Say, if we had specialized b to be Int, then we would have known everything about it, namely its constructors, and thus we could have simply returned 0 (or any other integer).

However, by parameterizing for all types b we have made a strong statement: it has to work for all types b, and therefore we are not allowed to make assumptions about the capabilities offered by a concrete type that will replace b.

The only way to produce a value of type b is by applying the function a -> b that we have received as an argument. And to apply the function a -> b, we first need a value of type a, which again has to work for all types a, and thus we cannot produce values of type a.

Fortunately, we have a list of elements of type a and we know everything that is to be known about lists, namely how to traverse it through recursion.

Therefore we can traverse the list of elements of type a, feeding each element into a -> b, and collecting the resulting bs into a list, which we then return.

The central part is:

Parametric polymorphism imposes strong constraints on the implementation.

When we implemented map, we stated that it will work for all types a and b, and we did not impose any requirement on a or b, e.g. via typeclasses, therefore nothing can be assumed about a or b.

In other words, when implementing map we did not know what concrete types will replace a and b, that decision deferred to users of map. They will decide this later when using our map function.

This is all assuming that bottoms do not exist in Haskell, e.g.

map _ _ = undefinedis not permitted.In this discussion, I will be ignoring bottoms completely.

We have looked at map from a user’s perspective. However, thanks to constraints imposed by parametric polymorphism, we also have gained an intuition on how to implement map “for free”.

The whole description so far translates into something that resembles the following snippet:

map :: (a -> b) -> [a] -> [b]

map _ [] = [] -- Base case: empty list in, then empty list out.

map f (x:xs) = f x : map f xs -- Recursive case: applies `f` to the first element (`x`) and prepends it with the result of the recursive invocation of `map` with the rest (i.e. tail) of the elements in the list (`xs`).

Let’s use map to add 10 to each element of a list of integers ranging from 1 to 5 (λ is my GHCi prompt):

λ map (+10) [1..5]

[11,12,13,14,15]

Filtering Elements

That was map.

Luckily we have plenty of other higher-order functions. And of particular interest for this post, we shall be considering filter:

filter :: (a -> Bool) -> [a] -> [a]

As opposed to map, I generally cannot instantly tell what exactly filter does. Sadly, I struggle for a few seconds with the question:

Does

filterkeep the elements for which the predicate holds or for which the predicate does not hold?

That’s not always entirely clear to me when I come back to Haskell after a little while away from it.

Next to its name, I tend to look for clues at its type.

Give me a function of type

a -> Bool(i.e a predicate) and a list of elements of typea, then I shall return you a list of elements of typea.

filter returns a list of type [a], presumably drawn from the input list, which also has the type [a]. How?

The type of the predicate does not tell us much in this regard, it returns just a boolean. Perhaps filter keeps elements for which the predicate evaluates to true. Although, in theory, it could very well keep elements for which the predicate evaluates to false.

More concretely, given a function even that checks whether an integer x is even:

even :: Int -> Bool

even x = x `mod` 2 == 0

What should the following program print?

λ filter even [1..5]

That would either be [2, 4] (even evaluates to true) or [1, 3, 5] (even evaluates to false).

Turns out that filter returns [2, 4]! That is, all elements x from the input list [1, 2, 3, 4, 5] for which the predicate even x evaluated to true.

Consequently, here’s how an implementation of filter might look like:

filter :: (a -> Bool) -> [a] -> [a]

filter _ [] = []

filter p (x:xs)

| p x = x : filter p xs

| otherwise = filter p xs

Disclaimer: I am not trying to make a case against

filterat all. I use it and I like it. Rather, I want to discuss the importance and beauty of types when it comes to type-driven API design.

filterjust happens to serve as a fairly contrived example that came to my mind.

Differently of map, the type of filter imposes fewer constraints on the implementation, which opens up for the possibility of mistakes. Say, for any type a, filter produces a list of elements of type a, but it still cannot conjure up values of type a. However, it happens to have an input list of values of the same type a, which it could just blindly (and mistakenly) return:

filter :: (a -> Bool) -> [a] -> [a]

filter _ xs = xs

Thus, filter did not filter anything at all!

That might strike as a “naïve and rather obvious mistake”. However, sometimes the most annoying bugs are caused by “naïve and rather obvious mistakes”. However, those mistakes are usually only deemed “naïve and rather obvious” only after we’d spent hours (days?) debugging and finally have fixed them.

Constraining APIs with Type-Driven Development

The type of filter could have told us more about what it does, and as a valuable side-effect (no pun intended) imposed more constraints on the implementation, such that illegal states would become unrepresentable.

Making illegal states unrepresentable is a famous statement, with powerful consequences. The intuition behind it is as follows:

We want to be as precise as we can when designing the types that we use in our APIs, such that classes of invalid usages of the API would be rejected by the type-checker and therefore the program would not compile successfully.

In other words:

The sooner I catch an error, the happier I am.

By being carefully precise, we start our design with types, letting them guide our implementation and enforce invariants. The more precise the types we use are, the more constraints we can impose and more knowledge we provide to the type-checker, which verifies these constraints for us.

The type-checker is our programming assistant.

We are pair programming with the compiler.

That’s the basics of Type-Driven Development (or Design?), or rather the part of the whole story that we are concerned in this post.

Let’s see how we may apply the idea to develop our own version filter, which we will initially call magic.

Starting off with the same type of filter:

magic :: (a -> Bool) -> [a] -> [a]

We produce a list of as from another list of as.

However, we want to distinguish between the type of the input list and the type of the output list, and hereby not be able to simply return the input list unfiltered. Taking inspiration in map, let’s change the return type from [a] to [b]:

magic :: (a -> Bool) -> [a] -> [b]

Cool. Now the wrong implementation we saw previously would not compile:

magic :: (a -> Bool) -> [a] -> [b]

magic _ xs = xs

Generally, we cannot prove that types a and b are the same (remember, the decision of which concrete types will replace a and b is made later, and not by us implementing magic, but by the users of magic), and thus the type-checker correctly rejects our program. That’s a win!

Again, it all boils down to the fact that parametricity is a strong promise.

When we say that a function has to work for all types

a, we cannot make assumptions on any capability offered by concrete types, which we don’t know about beforehand. In particular, we do not know what the constructors of some concrete typeawill look like, and thus we cannot even produce values of typea.Parametric polymorphism is a powerful and remarkably well-crafted tool to design type-safe APIs.

Oh, wait! We cannot just produce values of type b out of nowhere. Further, without any means of producing values of type b, we cannot implement magic at all. We have made progress, but we are not quite there yet.

Standing on the shoulder of giants once more, we see that map requires a function a -> b, which is the unique source of wisdom that knows how to produce values of type b from a. Instead of a -> b, magic requires a -> Bool, as it needs to filter elements (that is its purpose, after all).

Consequently, we could accept an additional function that knows how to produce bs from as. Perhaps something along the following lines would do it:

magic :: (a -> Bool) -> (a -> b) -> [a] -> [b]

In addition to the predicate a -> Bool, we require a second function a -> b, which we could apply to each element a at which the predicate holds.

Even though that would work, it might be inconvenient to use (e.g. magic needs to access the same element x twice, first to check and then to map), and confusing to understand (we have two functions as parameters).

Still, we have made some more progress.

What if we could collapse a -> Bool and a -> b into a single and simpler function while preserving their semantics? Turns out we can!

The function we want must be able to tell whether an element of type

ashould be “kept” (or be “thrown out”).Moreover, if the element is to be kept, then the function must map it into another element of type

b.

According to the Algebra of Types, we can use Maybe.

Maybe is an ADT equipped with two constructors:

data Maybe a = Just a | Nothing -- Either holds an element of type `a`, or nothing at all.

Namely, we could pick a function a -> Maybe b, where given a value x of type a, the function either returns Just b if we should keep x in the return list, or Nothing if we should throw x out:

magic :: (a -> Maybe b) -> [a] -> [b]

It is similar to map, but not quite.

Now, the only way to produce a value of type

bis by feeding a value of typeaintoa -> Maybe b. Further, we only have abwhena -> Maybe breturnsJust b.

That imposes a bold constraint on our implementation. If we “follow the types”, the implementation becomes a translation of the free-form description into Haskell code:

magic :: (a -> Maybe b) -> [a] -> [b]

magic f (x:xs) = let ys = magic f xs in -- Recursive case: recursively calls `magic` with the rest of the list (`xs`).

case f x of -- Base case: applies `f` to the first element (`x`) and prepends it into the list if it's in a `Just`.

Just y -> y : ys

Nothing -> ys

Optionally, for the sake of completeness, we can make magic a bit shorter by implementing it in terms of foldr with point-free style:

magic :: (a -> Maybe b) -> [a] -> [b]

magic f = foldr step []

where step x ys = case f x of

Just y -> y : ys

Nothing -> ys

If we define another version of the function even, which now returns a Maybe Int, instead of a Bool:

even :: Int -> Maybe Int

even x = if x `mod` 2 == 0

then Just x

else Nothing

Then we can use magic:

λ magic even [1..5]

[2,4]

Cool. We have implemented magic and designed its API with more constraints in-place, such that some wrong implementations will not compile at all.

Win-win, we may say.

Finally, the type (a -> Maybe b) -> [a] -> [b] suggests what magic does and even gives us an idea on how it does. Ultimately, it may offer us ideas on how to name it!

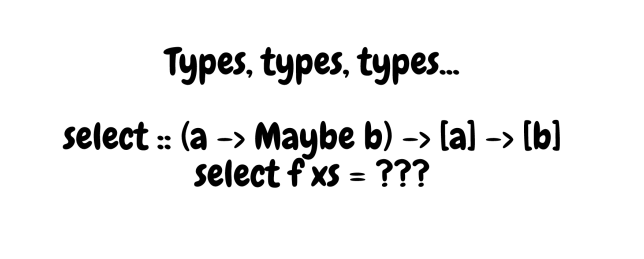

Here, I have chosen select:

select :: (a -> Maybe b) -> [a] -> [b]

Luckily, we do not even need to implement select ourselves, since Haskell ships with Data.Maybe.mapMaybe, which does the same thing.

Implementing filter in terms of select

Our select is expressive enough that we can even implement filter in terms of it. Let’s compare their signatures:

select :: (a -> Maybe b) -> [a] -> [b]

filter :: (a -> Bool) -> [a] -> [a]

We need to write a function, say toMaybe, that maps a -> Maybe b into a -> Bool, while preserving the semantics of the predicate. That is, Just y (a y of type b was produced from an x of type a) maps to True (predicate at x holds), and similarly Nothing maps to False. Well, we have already done it, and we now need to translate this description into Haskell:

filterInTermsOfSelect :: (a -> Bool) -> [a] -> [a]

filterInTermsOfSelect p = select toMaybe

where toMaybe x = if p x

then Just x

else Nothing

Trading Booleans for Evidence

At this point, let’s pause for a moment and revisit the two versions of the function even that we have previously defined:

even :: Int -> Bool -- Predicate.

even :: Int -> Maybe Int -- "Evidence".

When we call even x, we are attempting to prove whether x is an even number or not:

- If the predicate evaluates to

True, then we know thatxis even. - If the function produces a

Just x, then we know thatxis even.

Assuming a correct implementation, after we have called even x, we know for sure whether x is even or not. However, unfortunately, we throw that knowledge away immediately afterwards.

Say we have a function foo that accepts some integer x, checks whether x is even, does something with it, and then calls bar passing x as an argument:

foo :: Int -> IO () -- `IO ()` means that the only reason we call `foo` is because of its side-effect.

bar :: Int -> IO () -- Ditto.

-- Somewhere inside `foo`:

foo x = -- ...

bar x

Furthermore, let’s say that bar also depends on x being even to complete its job. The question is then:

Should

barcalleven xagain? Or should it trust thatfoohas already done that before?

The decision might be trivial in small programs, bar could simply trust foo and not call even again. However, as the program grows, with calls going through different modules (say foo calls foo1, which calls foo2, …, which calls foo10, which then finally calls bar), then matters become far more complicate.

As time goes by, we might decide to refactor the code. Perhaps we notice that foo itself does not really care whether x is even anymore, so we clean it up and naively remove the call to even inside foo, but forget to update bar (which now must call even). Sadly, an “innocent” refactoring at one point broke the code located in a fairly remote place.

Spooky action at a distance! The enemy of local reasoning.

Fundamentally, bar had a pre-condition on x being even, but it did not make that pre-condition explicit. Not at least as far as the type-system is aware.

We want to restructure our code in such a way that failing to pass an even integer to bar triggers a compilation error.

The predicate version even :: Int -> Bool cannot help us at all, because booleans are not expressive enough to preserve the knowledge that we need.

However, its alternative even :: Int -> Maybe Int can! We just need to push it a little farther.

As we have said before, a

Just xproduced byeven xcan be considered as evidence thatxis even.

Hence, by following a type-driven approach, we could pick a type other than Int for a in Maybe a. That is, a special type like a, but equipped with the semantic:

Any value of this type must be even.

We may call such a type EvenInt:

Any value of type

EvenIntmust be even.

Luckily, Haskell makes this task quite straightforward with the “newtype pattern”, where we introduce a newtype wrapping our primitive Int:

newtype EvenInt = EvenInt Int

deriving Show -- deriving it from `Show`, so that we can print values of type `EvenInt` to the console.

Thus, we may re-write even as:

even :: Int -> Maybe EvenInt

even x = if x `mod` 2 == 0

then Just $ EvenInt x -- Additionally to what we had before, we now wrap `x` (`Int`) into an `EvenType` to preserve the evidence that `x` is an even number.

else Nothing

Notice that nothing has changed, except that we are wrapping the primitive integer x in an EvenInt.

Once we call even x, we not only know whether x is even or not, we are also preserving this evidence (knowledge) in the return type EvenInt! We can thus pass the evidence to other functions down the chain, which would accept EventInts, instead of plain Ints, and thereby be sure that the argument is even indeed.

EvenIntis the subset ofIntsuch that members (values) of typeEvenIntmust be even integers. That is,EvenIntnarrows (restricts) the domain of valid values of typeInt.In symbols:

EvenInt = {x ∈ Int | x is even}

Back to our example, bar would accept an EvenInt:

bar :: EvenInt -> IO ()

The precondition that bar has on x to be even is made explicit on the type of x.

Therefore foo must call even x in order to get an EvenInt from it, which foo then supplies to bar. If foo had failed to call even and instead tried to pass a primitive Int to bar, then the code would not have compiled.

We have restored our ability to reason locally about our code.

evenmight be called a smart-constructor, where we attach extra meaning to some primitive type (e.g.Int) by wrapping it inside another type (e.g.EvenInt) with more constraints (meaning) than the primitive type that it wraps.Furthermore, the type

EvenIntand its smart-constructorevenshould be properly encapsulated inside a module to limit visibility, such thatevenwould be the only place where we can obtain instances ofEvenInt.

Conclusion

The principles behind pretty much everything that we have seen in this post are parametricity and proper mapping of concepts into strong types.

When we quantify a property for all types, we are making a bold statement, which has to hold for whatever concrete type we feed into the property.

When we introduce a data type that precisely and unambiguously models a given concept in our domain and restricted where and how we are allowed to produce values of that type, we can treat such values as evidence that we have satisfied some property.

Say, if a domain involves product identifiers and quantities, instead of representing both product identifier and quantity as raw integers, we are probably better off introducing the types ProductId and Qtd, wrapping primitive integers.

Luckily, programming languages such as Haskell come with a concise notation for this very purpose:

newtype ProductId = ProductId Int

newtype Qtd = Qtd Int

Equipped with parametricity and types that precisely maps to our domain objects, we have managed to encode useful information at the type-level, which was then translated into discipline imposed on the implementation. Ultimately, we let types drive our design.

Furthermore, types serve as “extra-specification”, which is automatically verified by the compiler. Consequently, as a good specification, it can help other programmers reading our code and trying to reason about it in isolation (locally).

Types are not only about imposing discipline on programs, but also about communicating ideas and guiding usage.

For example, a function such as:

buy :: Int -> Int -> IO ()

Would probably better communicate what it does if written as:

buy :: ProductId -> Qtd -> IO ()

Further, it would be harder to use incorrectly:

let bookId = ProductId 10 -- Instead of `bookId = 10 :: Int`.

let totalBooks = Qtd 3 -- instead of `totalBooks = 3 ::Int`.

buy totalBooks bookId -- Oops! I meant `buy bookId totalBooks`.

This snippet would erroneously compile in the former version of buy (with primitive integers), but correctly fail with a clear type-error due to type mismatch in the latter (with stronger types), such as:

Couldn’t match expected type

ProductIdwith actual typeQtd.

Thereby preventing a bug from slipping in.

Prefer to turn potential run-time errors into compile-time errors. Allow the compiler to give you feedback about your code.

By following a type-driven design approach, we have used types to express a plan (what we want to accomplish), then we implement the program (how we want to accomplish) in such a way that the types (plan) must be satisfied. The type-checker becomes our assistant and verifies properties along the process for us.

However, that comes at a cost. Arguably, both type-signatures and implementations may have become more complex, and we may have mixed two concerns (predicate + transformation). Being pragmatic, in some cases a less precise design may serve us just as good.

Even though we have used Haskell in this exposition, the underlying principles should hopefully translate to other languages, such as Rust, Scala, etc. Further, languages with even more powerful type-systems (e.g. Agda and Idris, both with native support for dependent types) allow us to encode many more properties.

It is important to emphasize that:

Type-Driven Development does not substitute proper automated tests, rather they collaborate. Moreover, unit-tests could (and should) have caught the mistakes in the wrong implementation.

Conclusively, it is much better to combine types with tests.

Nevertheless, I very much like letting types help with my design. Mainly the relief when the type-checker denies my broken code due to a type-mismatch caused by a wrong refactoring.

Summing up, it is all about bringing extra safety guarantees and thus increase our confidence that the code is correct.

References

[1] Programming Language Foundations in Agda.

[3] Idris: A Language for Type-Driven Development.