Emulating pattern-matching in a language without native support for it.

|

|---|

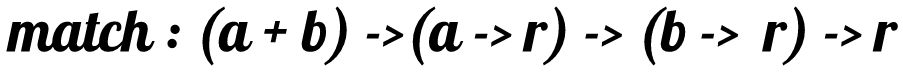

| Match as a function (a + b) -> (a -> r) -> (b -> r) -> r. |

Pattern-matching, also known as case-analysis, allows us to deconstruct terms into their components with a syntax (and semantic) suitable for data-oriented queries and/or define algorithms over types of different yet related shapes.

This improves the navigation and processing of data structures through external algorithms. It’s particularly useful when we want to apply an open set of functions on an Algebraic Data Type with a closed set of immutable variants of a known schema, henceforth separating the data from the behaviour we may later (in time and/or space) associate with it. This comes as a subtle, yet fundamental, contrast with objects. In terms of objects, there’s usually a closed set of virtual functions operating on an open set of types, typically dispatched through an interface, thereby consolidating data and its associated behaviour as a unit. Much of this contrast is nicely summarized in the so-called Expression Problem.

Pattern-matching is commonly reified as a language feature in programming languages that encourage the functional style of programming (e.g. Haskell, Scala, OCaml), even though it’s oftentimes feasible to emulate it in Imperative languages (e.g. C++, Java, C#) with the Visitor pattern or similar encoding. Nevertheless, given the benefits of having native pattern-matching constructs, we’ve been seeing some widely used imperative languages pushing to include pattern-matching capabilities in their set of features. For example, there’s Rust and perhaps Java or C++ in the future.

Actually, Java has had some narrow support for pattern-matching within

catchclauses, where we match against a set of exceptions and react upon a successful match depending on the corresponding handler.

Support for native pattern-matching streamlines a tighter integration with the rest of the programming language and therefore may offer a more comprehensive and ergonomic experience with higher levels of expressiveness.

However, it’s sometimes possible to get away with an appropriate encoding by emulating pattern-matching in the language where this is lacking (or where this feature is not yet available). Today, I briefly present one such encoding with the Visitor pattern expressed in the Java programming language. And, as a bonus, we shall also see the Scott encoding of data types from which we gain support for pattern-matching in a perhaps surprising form.

IMPORTANT: Throughout this contrived example, keep in mind that this exercise is only meant for learning and not necessarily for building on idiomatic (or efficient, battle-tested, production-ready) uses of Java. Particularly, the path we will take to model a list is most likely not what we should reach out for solving real-world problems.

Pattern-matching Algebraic Data Types

For illustrative purposes only, let’s entertain ourselves with a rather contrived use case for which we’ll come up with solutions in Java in terms of pattern-matching:

Assume for the sake of this exercise that we want to model a singly linked list as an inductively defined Algebraic Data Type (defined by cases) and then write a couple of external (“free-standing”, not attached to a class/object as methods) functions over it.

For instance, given a list of integers, we want to compute the sum of its elements (or maybe we could map the elements with a function, or filter its elements, or compute its length, etc; but for brevity we shall only implement the summation).

In terms of a simplified algebraic notation, we may describe our list L as:

L(a) = 1 + a * L(a)

This reads as a singly-linked list

Lof homogeneous elements of typeais either (+, also known as variant, sum, or co-product) empty (1also known as unit) or it’s composed of the pair (*also known as product) of a term of typea(also known as head) and the rest of the listL(also known as tail) of elements of typea.

Or, in a typical ML language with native support for ADTs such as OCaml:

type 'a list = Nil | Cons of 'a * 'a list

Finally, an equivalent (with labelled fields) representation in Java:

// IMPORTANT: This representation is only meant for pedagogical purposes.

// For a production system, we are most certainly better served with a JDK collection,

// such as the ones backed by dynamic arrays or even optimized linked nodes.

sealed interface SList<T> {

record Nil<T> () implements SList<T> {}

record Cons<T> (T head, SList<T> tail) implements SList<T> {}

}

The

sealedmarker informs the type-checker (and the human reader) that there’s a closed, known set of types satisfying theSList<T>interface; and equipped with this knowledge, the checker can ensure niceties such as exhaustive coverage, etc.

With the type defined, we move on to actually implementing sum within which we pattern-match.

Native Record Patterns

Our goal is to write the function sum:

sum : L(integer) -> integer

We may implement it in a language with native support for pattern-matching such as OCaml directly by pattern-matching on the list parameter:

let rec sum list = match list with

| Nil -> 0

| Cons (head, tail) -> head + sum tail

IMPORTANT: This, as well as all the other recursive implementations in this text, are not tail-recursive and consequently susceptible to stack-overflows and performance penalties.

Or, with a sugared syntax, a little terser as:

let rec sum = function

| Nil -> 0

| Cons (head, tail) -> head + sum tail

The snippet above, albeit shorter, expands to the longer

match .. with ..we’ve seen previously.

Back to Java. As a first attempt, if we assume that we have access to the JEP, we may complete the assignment with something like this:

// WARNING: The following snippet depends on preview features.

class SListOps {

static Integer sum(SList<Integer> list) {

return switch (list) {

case SList.Nil<Integer> ignored -> 0;

case SList.Cons<Integer> cons -> cons.head + sum(cons.tail);

};

}

}

Notice the recursive definition of the algorithm. We match on our list parameter of type SList<Integer> and:

- When we obtain

Nil<Integer> ignored, this means we’ve reached the base case; and therefore we map this term to0 - When we obtain

Cons<Integer> cons, this means we’re in the recursive case; and therefore we sum thecons.headof the current list with the outcome of recursing over thecons.tail(itself aSList<Integer>)

There’s a connection between the way we’ve defined the data structure and the way we’ve operated on it, where the operation “undoes” what the definition had done. More on this in a future post.

Visitor encoding

I’ll be showing just one among multiple ways to encode the Visitor pattern.

While we wait for the JEP graduate, or even afterwards, we might meet our goal with the help of the Visitor pattern, thereby compensating for the missing support for pattern-matching.

We can do that by observing the correspondence between a single function on 1 + a * L(a) (operating on the variant) and a pair of functions on 1 and a * L(a) (operating directly on the components). We shall call such a function accepting the pair as match - an alternative name would have been visit, but I’m sticking to match for the sake of consistency:

<R> R match(Supplier<R> caseNil, BiFunction<T, SList<T>, R> caseCons)

- When we match on

Nil<T>(), then we should invokecaseNil - When we match on

Cons<T>(head, tail), then we should applycaseConstoheadandtail

In this setup, the next step would be to attach match as a method of SList<T> and then implement it for Nil<T> and Cons<T> following the logic previously explained:

sealed interface SList<T> {

<R> R match(Supplier<R> caseNil, BiFunction<T, SList<T>, R> caseCons);

record Nil<T> () implements SList<T> {

@Override

public <R> R match(Supplier<R> caseNil, BiFunction<T, SList<T>, R> _caseCons) {

return caseNil.get();

}

}

record Cons<T> (T head, SList<T> tail) implements SList<T> {

@Override

public <R> R match(Supplier<R> _caseNil, BiFunction<T, SList<T>, R> caseCons) {

return caseCons.apply(head, tail);

}

}

}

Thus, we may now implement sum in terms of match as:

class SListOps {

static Integer sum(SList<Integer> list) {

return list.match(() -> 0, (head, tail) -> head + sum(tail));

}

}

And use it like this:

final var list = new SList.Cons<>(1, new SList.Cons<>(2, new SList.Nil<>()));

System.out.println(SListOps.sum(list)); // prints 3

Scott encoding

So far, we have always started with a data structure defined as an Algebraic Data Type and from that, we encoded a way to pattern-match it.

The Scott encoding works a little backwards if taken from that perspective, whereby we identify pattern-matching as an universal operation and therefore able to fully encode a data structure; hence we may elide the records entirely and take match as the data structure itself!.

We may express this idea in Java like this:

// WARNING: This does not compile (see note below).

@FunctionalInterface

interface SList<T> {

<R> R match(Supplier<R> caseNil, BiFunction<T, SList<T>, R> caseCons);

static <T> SList<T> nil() {

return (caseNil, _caseCons) -> caseNil.get();

}

static <T> SList<T> cons(T head, SList<T> tail) {

return (_caseNil, caseCons) -> caseCons.apply(head, tail);

}

}

Notice that we have dropped the

sealedmarker, since there’s really no type declaration implementing theSList<T>interface anymore.

No records! Actually, there are no longer any data structures as we probably think of them. Instead, we have only factory methods as opposed to records and closures filling in the role of data containers by capturing (or closing over) head and tail.

Unfortunately, as previously stated, this snippet does not compile at the moment. This happens because Java forbids lambda expressions from implementing generic interface methods (when the method itself introduces type parameters). However, we can work around it by simply expanding the sugared syntax for lambdas into anonymous inner classes:

interface SList<T> {

<R> R match(Supplier<R> caseNil, BiFunction<T, SList<T>, R> caseCons);

static <T> SList<T> nil() {

return new SList<>() {

@Override

public <R> R match(Supplier<R> caseNil, BiFunction<T, SList<T>, R> _caseCons) {

return caseNil.get();

}

};

}

static <T> SList<T> cons(T head, SList<T> tail) {

return new SList<>() {

@Override

public <R> R match(Supplier<R> _caseNil, BiFunction<T, SList<T>, R> caseCons) {

return caseCons.apply(head, tail);

}

};

}

}

That’s a little longer, but it does compile successfully.

With the working syntax ready, nothing changes in the sum function. The only step left is to patch the call-site to use the new factories instead of instantiating the records:

final var list = SList.cons(1, SList.cons(2, SList.nil()));

System.out.println(SListOps.sum(list)); // prints 3

Conclusion

We’ve seen how to emulate pattern-matching in a language without native support for it. Firstly, we used the Visitor pattern and then we even elided the whole classical data structures by representing them directly as a pattern-match with the Scott encoding of data types. Parallel to that, we had the chance of exploring a popular recursive algorithm and expressed the same concept with alternative notations. At the same time, we became familiar with different ways to encode the same solution and had a glimpse of what might become a new feature of Java in some upcoming release.

To be expressible, the Scott encoding imposes some requirements on the host language. For instance, if the language is statically-typed, then such a type-system must admit lambdas closing over lexical scopes (lexical closures) and the ability to define algebraic data types inductively (recursive data types). Java, among a couple of other programming languages, satisfies both criteria. There are also alternative encodings with different requirements and pros/cons, such as the Boehm-Berarducci encoding.

As hinted at before, emulating an otherwise natively supported language feature comes with its own tradeoffs. Namely, we don’t get all the expressiveness capabilities (e.g. nested patterns, guard clauses, aliases), ergonomics and synergy with the rest of the language; not to mention that we end up writing more code, possibly repeating ourselves across types and projects. On the other hand, at least this approach enables us to get going, should we need to follow this path.

Moreover, throughout this discussion, we have purposefully focused solely on abstract notions and ignored critical aspects of real-world systems, such as resource-efficiency demanded by a solution. As an example, if we apply the Scott encoding to model a data structure as a pattern-match, it would offer very different performance characteristics with regard to runtime when compared against a memory-efficient data structure optimised for real access patterns and digital computers.

Lastly, it’s worth emphasising that just because we can apply a technique, it doesn’t necessarily mean that we must or even should. In reality, different scenarios generally require different solutions where we should consider all relevant factors, such as surrounding language facilities and their idiomatic usage, supporting tooling, the larger ecosystem, existing code-base, familiarity and preference of the team, etc.

Personally, I wouldn’t recommend applying *all* techniques previously described without due consideration and taking the context into account, eg. sometimes dispatching through an abstract interface may be more appropriate than matching on a concrete type. As stated before, the goal of this post was, in part, to lean more towards the curiosity/trivia side of professional programming, also serving as an excuse for us to explore a variety of interesting topics, some of which inhabit the more theoretical areas of Computing Science.

All in all, I hope you’ve enjoyed reading this post as much as I enjoyed writing it!

References

[1] Algebraic Data Type and Data Modelling

[2] A Brief Introduction to the Algebra of Types

[4] JEP 433: Pattern Matching for switch (Fourth Preview)