The Beauty of Total Functions

The joys of APIs that don’t lie to us.

|

|---|

| 😱 Trust me, it’s not as scary as it looks. |

Granted, the title might sound fancy, I acknowledge that. But I have to tell, I do like total functions. It might sound super complicated, but the truth is: it’s reasonably simple. And once understood, they can make our lives easier. Most importantly, the idea behind total functions does not need to be 🚀 science. It’s practical and we should try treating it as such.

To exemplify things, I’ll be to using C++, although the same principles follow regardless of the programming language you may happen to be writing code in. Furthermore, I’ll try to keep the examples absent of complicate C++ features, therefore people not familiar with C++ would hopefully be able to follow along. Please, reach me out in case of doubts, I’d be happy to take questions or suggestions.

First Thing Come First, or Don’t They? 😔

Before we start talking about total functions, let’s first discuss why they’re useful in the first place. We will be exploring an example where we didn’t opt-in for total functions, the issues that might arise from the decision, and then at how total functions might help us.

Challenge 🏃:

Write a function

headthat receives a list of integers and returns the first element of the list.

In C++, we could write this function as:

int head(std::vector<int> elements) {

return elements[0];

}

(For the sake of brevity, I have omitted const, references, templates, etc.)

Should we say that our task is done? Maybe.

Corner Cases and Where to Find Them 😖

Let’s think about the following case:

- What happens when

elementsis an empty list?

If we look at the API (here defined by the signature), the types tell us nothing. As far as the types are concerned, anything may happen.

However, we know (or at least we have a “gut feeling”) that the function has to fail somehow in this case. The question then becomes:

- How does it communicate such a failure condition back to the caller?

Once again, the types don’t tell us anything, not a clue.

Let’s step aside for a moment and stop thinking about the implementation that we saw.

Pretend that we only access to the signature, say it’s a third-party library and we only got the headers with no documentation.

What does the signature tell us?

Give me an

std::vector<int>and I shall return you anint.

It promises that it’ll always return an int, no matter the input we’d provided.

head has plenty of options to fulfil such a strong promise.

Option 1: Return an “Invalid” Value (In-Band)

It could reserve of the possible return integers as “invalid” and return this invalid int when the list is empty. The exact “invalid” value is dependent on the exact context (e.g. -1, for a list of non-negative integers).

However, we must be entirely sure that such an invalid value does not have any other meaning in the application. Further, this assumption has to forever hold. If the invalid value suddenly becomes a possible valid value (e.g. we accept negative integers in the list), then we would be in trouble as there won’t be a way to tell error and expected result apart (e.g. element not found vs the first element in the input list was -1).

Even worse, we usually don’t have the “luxury” of reserving a value as invalid. Maybe all possible values do make sense for a given application and therefore cannot be wasted.

Moreover, how would we communicate such an invalid value is invalid (e.g. we return -1 if the input list is empty)?

Usually, this is done in a comment, which then becomes a liability that has to be forever maintained and kept up-to-date.

This may or may not a problem, though.

Option 2: Use an Out-Parameter

We could recur to an out-parameter and pass a reference (or a pointer) to an int that would then be set inside the function if elements is not empty, and return a bool to communicate whether the value was correctly (return true) set or not (return false). We could very well go the other way around, and pass the bool by reference and return the int through the return statement.

This approach comes with its drawbacks:

- It mutates an external parameter.

- It entangles control flow with error handling.

- It may prevent inlining, which may degrade performance.

- It doesn’t compose nor scale well.

Furthermore, given that the bool and the int are not strongly bound to each other, we might forget to check the former before latter.

Option 3: Return a Pointer

We could return not only an int but rather a pointer to an int, which brings a blurred concept of nullability.

In this case, a pointer to an int allows all values that an int allows plus one: the absence of any value, i.e. nullptr.

In terms of Algebraic Data Types, this translates to:

#Pointer_to_Int = #Int + 1

However, this decision also has its issues. The fact that we are using a pointer to express the absence of a meaningful value (that is, an error) might not be that apparent, since a pointer also has overloaded semantics, e.g. late dispatching, dynamic memory allocation, etc.

More critically, pointers are powerful, and returning a pointer opens up the door to lifetime and resource management, which would complicate our code significantly. That would be unfortunate because we don’t need most of the powers that pointers have.

Option 4: Throw an Exception

Another option, which may the obvious (and sometimes the right) one, is to throw an exception when an empty list is passed in.

From my perspective, this is far more robust than the previous ones, if you can afford exceptions.

However, exceptions are usually better off when applied to truly exceptional scenarios. The definition of exceptional is bound to your specific use-case.

I’m not focusing on performance, but rather on semantic:

Would you say that passing an empty list is an exceptional situation?

If the answer is no, but we still use exceptions, then we may be using exceptions for flow-control, which might not be a good idea.

Another drawback of exceptions is that we run the risk of being too eager when already trigger an exception at this point, we may not have all the information and context to decide it straight away.

For instance, head might be a utility function deep inside a helper library far away from the main application where the user has more information to make better decisions. But if we throw an exception and the user forgets to handle it by wrapping the call in some sort of try/catch block, then the stack unwinding will go up to the first point where it’s handled or crash the application if it’s not handled at all.

Thus, instead of deciding on our own, we could push it to the client, which could then push it further to its client, and the process recurses up to the border of the application (e.g. the UI), where we might have more information to decide what we should do.

Essentially, exceptions might be too implicit and nothing assures that callers must handle, or explicitly ignores to allow propagation, them.

I am not against exceptions, not at all, they do have plenty of use-cases.

The implicitness of exceptions is a double-edged sword. It comes with its cons, e.g. nothing ensures handling; but also pros, e.g. the source of an error and its proper handler might be many layers away from each other.

Enough of Options for Now

Bonus: There are other, possibly reasonable, options: assert, kill the thread, terminate the whole process, etc. But we won’t be covering them for the sake of time.

As usual in programming, each option comes with pros and cons, and it’s up to us, programmers, to make our calls. However, up to some extent, they all share a common issue, which was briefly mentioned:

The fact that the function might fail is not part of its API (as far as the types are concerned). Thus, we have to rely on some external information: comments, implementation, etc, should we want to understand what happens in the case of a failure.

Further:

Even if we do know what happens in the case of a failure, the type-system is not aware and thereby cannot enforce that clients handle failures properly. Or, at least, they acknowledge that such a failure might occur.

The options below attempted to somehow encode the failure in the API, but they were not as clear as they could have been:

- To use an out-parameter combined with a flag.

- To return a pointer.

Back to Our Example ☺️

I’d like to stress out what I meant when I cited the type-system:

Assume that we’ve changed the signature to return a pointer and we used nullptr to express the absence of a meaningful value (i.e. list was empty). Once again, to keep things short, I’m going to use a plain raw pointer, rather than a smarter one.

Meanwhile in the caller code, the user accidentally forgot to check against nullptr before accessing the returned value:

int* head_of_list = head(std::vector{});

use(*head_of_list); // Oops! I forgot to check. Bad, bad user!

Oops, we’ve got ourselves into troubles! 💥

We de-referenced a nullptr, a cardinal sin. In C++, we bought our ticket to the troubled land of Undefined Behaviour (UB) 🎢, where anything can happen. If we’re lucky, this will crash, but nothing guarantee that at all. Hence, we should not rely on this particular behaviour. We should expect anything; in particular, the worst.

Okay, the type-system sort of tried to warn us:

- We had to dereference the pointer (through

*) to access its underlying value.

To my mind, that’s a bit of a hint. Although, as I said before, we could have returned a pointer for a different reason than to express nullability (again, we would probably need to rely on documentation or access to the implementation). We’re not being as precise in telling what happened:

headneeds to tell the caller that it may fail to return anint.

The issue with pointers maybe even more subtle in programming languages where everything is implicitly behind pointers. That’s particularly trick when nullptr (or its equivalent, e.g. null) can inhabit in all types (e.g. non-primitive types in Java).

This all means that we don’t need to explicitly dereference the pointer to make use of its content, hence almost everything may contain null.

Therefore, our humble hint to check for emptiness might not be as rock-solid as we’d wished for 🚢.

What Happens in our Original Example? 😄

In C++ pretty much anything can happen when we try to access an array outside of its bounds. Put more formally:

Accessing an element of

std::vector<T> vecat indexi, which is out-of-bounds (i.e.i ≥ vec.size()) is undefined behaviour.

Should have we wanted to make that code more robust, we could’ve chosen at(i), instead of operator[], at(i) does bound-checking and throws an exception when the size-constraint is violated.

That’s better. Yet, it’s still an exception and we didn’t deem empty lists as exceptional scenarios.

Beyond that, we wished that type-system could assure that users would handle empty lists adequately.

We can haz our wish granted, plz? 😿

Finally, Total Functions 😉

Let’s review our assumptions:

headmay fail due to an empty-list.- Such failure is not exceptional.

- We want to be explicit and have the type-system enforcing error handling.

Therefore we want to communicate the chance of a failure at the API-level and entrust the type-checker to enforce guarantees statically.

Thus, callers must handle failure conditions. Or at least be aware that the function may fail, and be explicit and conscious, should they opt-in to ignore the failure.

We don’t accidents on our shift! 💂

How can we do that? As the title hints: total functions all the things.

A total function can be regarded as:

A function where, for every possible value of its parameters, it always succeeds to produce and return a value that matches the return type. Therefore, such functions are defined for every single possible input value.

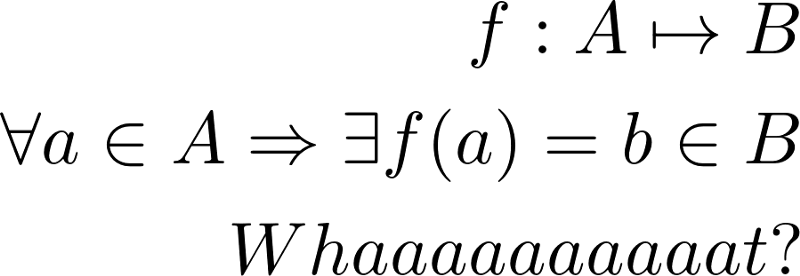

Mathematically speaking 📜:

A function f is a mapping from a set A (domain, source) to another set B (co-domain, target). Symbolically:

f: A ↦ B

The function f is total if:

∀a ∈ A, ∃b ∈ B : f(a) = b

That is, f is well-defined for every possible input value a and it returns a value b that matches its return type.

If f is not total, we say that it’s partial:

∃x ∈ A : ∄f(x) ∈ B.

This means that the function is not well-defined (i.e. fails) for one (or more) value(s) of the input type.

In programming we usually don’t talk directly in terms of sets, we rather talk about types, which might be thought of “proxies” to sets.

Back to our example:

An empty

std::vector<int>{}is a value of the typestd::vector<int>.

Therefore, we can provide an empty list to head, after all that’s a valid value like any other value (e.g. std::vector<int>{1} or std::vector<int>{1, 2}). However, the function not well-defined for an empty, it fails badly.

We have to communicate that head may fail.

Fortunately, we can straightforwardly turn our partial function into a total by choosing a return type that admits all the possible values that int admits plus “nothing” (i.e. the absence of a meaningful value). It’s similar to returning a pointer, but we’re looking for a type whose only purpose is to express the nullability.

In C++, the type we’re looking for is std::optional<int>. It has a “similar” purpose to Scala’s Option.

Essentially:

A value of type

std::optional<T>either contains a value of typeTor it’s empty.

By lifting the return type into an std::optional<int> as opposed to an int, we can change the signature of head:

std::optional<int> head(std::vector<int> elements)

This new signature precisely expresses the semantics that we were looking for.

std::optional<int> represents a value that may (function succeeded) or may not be there (function failed).

Now, the API says:

Hey, this function may fail, in which case it returns an empty optional. Or if it succeeds, then it returns the value wrapped inside the optional.

Great! The signature clearly expresses what happened.

A possible implementation could then be:

std::optional<int> head(std::vector<int> elements) {

if (elements.empty()) {

return std::nullopt;

}

return std::optional{elements[0]};

}

If elements is not empty, then we return an empty optional (std::nullopt). Otherwise, we access its first element (at this point we’re sure it’s not empty because we’d checked that before) and then returns it wrapped in the std::optional<int>.

Meanwhile, in the caller code, if the client tries to use the value directly as:

use(first_element);

The code will not compile!

The type-checker enforces that the user must acknowledge that the function might’ve failed. If one forgets to acknowledge then the type-checker won’t be forgetful and shall readily trigger a compilation error as we’ve been wishing for.

One way to handle the error may be:

std::optional<int> first_element = head(std::vector<int>{});

if (first_element) {

first_element.value();

}

else {

/* The response to the error goes here. */

}

Now, the user has to be explicit and invoke value(). The user has to forcefully think about what should be done to handle the failure condition. If the user still forgets to check for the error, then value() raises an exception.

It’s also possible to access its value through

operator*, which is similar to a pointer (invokes U.B when the optional is empty). We may say that its name is way too short (just a single character) to express its meaning, which might get obfuscated. Perhapsunsafe_get()would be a better name? Anyways, sometimes it’s useful, especially when it immediately precedes the check for emptiness.

It’s also possible to provide a default value that is returned as a fallback when the std::optional<int> is empty:

first_element.value_or(0) // If optional is empty, then value_or returns 0.

Of course, it’s still possible to directly access the wrapped value without even checking it before. But if we do, then we must be explicit.

So, don’t 🚨, just don’t recklessly access an optional without making sure that you’ve checked it before.

Is this the Best Solution? Not Necessarily 😮

We have turned head into a total function by enlarging its return type, thus extending the set the possible values that it can return. We have worked on the function co-domain, making it larger to accommodate an empty object that matches the return type.

Another possibility is to shrink the parameter type and reduce the set of possible values that it can accept. Thus, we would work on the function domain, making it smaller and disallowing the empty list that would not match the parameter type.

Therefore, rather than accepting an std::vector<int>, we could use a stronger type that cannot possibly be empty.

This might not be that common, but it exists and is used in some programming languages, say NonEmptyVector present in the Scala library cats 😸. A NonEmptyVector always has at least one element followed by an optional “tail” of elements.

From my perspective, that is an even better approach, since the illegal state can’t be represented in the first place. We don’t push the burden of handling the error onto the caller after he had called us, instead, he has to handle it before calling us. Usually, this leads to our caller pushing the burden further to his caller and so on, ultimately this ends up at the border of our program (e.g. UI, REST endpoint, or database), which would be the only place where the conversion list to non-empty list happen and thereby our program (except for this thin border) becomes “free” of empty lists.

Although slightly more complicated, shrinking input types is a great approach to solving problems and ensure data validity. Hopefully, I will have time to cover it properly in future posts 🔜.

Bonus: How about Composition? 😍

A thing that may be frustrating when using std::optional<T> in C++ is that it doesn’t compose quite as nicely as in other programming languages (e.g. Haskell’s Maybe, Scala’s Option and Rust’s Option’).

Consider an API that makes use of std::optional<T>.

We might then have the following functions:

std::optional<person> find_person();

std::optional<address> find_address(person const&);

zip_code get_zip_code(address const&);

A common pattern in C++ could then be:

auto person_opt = find_person(); // (1)

if (!person_opt) return; // (2)

auto address_opt = find_address(*person_opt); // (3)

if (!address_opt) return; // (4)

auto zip_code = get_zip_code(*address_opt); // (5)

- We found the

person. - Then we checked if it’s not empty.

- Then we found the

addressgiven the previously foundperson. - Then we checked if it’s not empty;

- Then we found the

zip_codegiven the previously foundaddress.

The checking for emptiness (steps 2 and 4) clutters our logic and affects readability. Ideally, we would check for emptiness only once, at the end of the whole chain (where we would then take an action), rather than having the error path entangled with the happy path.

Moreover, each check introduces additional complexity and it’s susceptible to mistakes, where we forget to cover one check.

It’d be nice to compose the operations and only check if something went wrong at very the end.

Fortunately, C++ may get a nice monadic interface to std::optional<T>!

Besides having a scary name, a monadic interface roughly means that we’d be able to compose several std::optional<T> as we do with the types that they wrap.

In the meantime, there are alternatives we could profit from. My tiny library absent may be one of such.

absent is a tiny open-source header-only library inspired in the declarative style encouraged by programming languages such as Haskell and Scala.

I wrote absent with the main goal of lifting std::optional<T>, or rather any std::optional<T>-like type as long as it adheres the expected API, into a monad that can easily be composed into a chain of operations.

Equipped with absent, the example may be re-written using an infix notation as:

auto zip_code_opt = find_person()

>> find_address

| get_zip_code;

if (zip_code_opt) {

/* Use the value. */

}

else {

/* Handle its absence. */

}

NOTE: It’s also possible to use named function (

and_thenandtransform, instead ofoperator>>andoperator|, respectively).

Now, the check is done only once, in the end. That’s what we wanted.

The chain of calls fails fast, which means that if any of the intermediate steps returns an empty optional, no further function shall be called, and an empty optional will be returned as the result of the whole chain.

Therefore we don’t need to check for every single step, absent handles this for us. That simplifies our code and reduces the surface on which bugs can break-in.

Further, absent offers a few more features, for instance:

- Several combinators (

for_each,eval,attempt, etc) for different scenarios. - Possibility of adapting custom

std::optional<T>-like types to work with absent.

absent is a new and tiny project and hence lacks plenty of features and improvements, but it may be helpful in some circumstances.

Needless to say: an open-source project, you’re more than welcome to submit PRs with suggestions and improvements.

I will look forward to your patches 👐.

Conclusion

We’ve seen the importance of writing total functions, their benefits and what could go wrong if we forget to think about error conditions.

Of course, there’s no silver bullet. Sometimes we may need to resort to other alternatives, e.g. exception might fit some bills better.

In summary, I’d suggest to:

- Strive to write APIs that convey the necessary information for users to understand what happens not only in that “happy path” but also when things go wrong.

- Prefer to fail at compile-time rather than at run-time (not always applicable or desirable).

- Check for errors and prefer to define a uniform error handling upfront.

- Be pragmatic and use your judgement. Know your tools and pick what is best for each requirement.

- absent may help to compose optional-like types in C++.

If the programming language offers a static type-system, then we should make use of it by mindfully designing and selecting proper types to convey our assumptions. Thus, we can leverage the type-checker to enforce guarantees on our behalf and make users aware of them.

Last, but not least, in our head example there was one and only one possible failure (empty list, represented by the empty optional), hence clients could unambiguously infer the reason why the function failed. More generally, that’s not always true, we usually deal with functions that may fail due to several reasons. For these cases, we should go for a more powerful type than an std::optional<T>.

Particularly, we look for a type that allows us to express one among different failures. This might be a job for an std::variant<Ts...> (C++), Either l r (Haskell), Result<T, E> (Rust), etc. The solution would look similar to what we saw when we talked about ADTs. However, this post is already lengthy enough, so the treatment will be a topic for another day 😉.

Stay tuned.

References

[2] A Brief Introduction to the Algebra of Types.

[3] absent.

Originally published at https://medium.com/@rvarago